What does climate change mean for the Mystic?

Photo credit: Erica Wood

We are a Greater Boston coastal watershed. We are learning to adapt to more intense rainfall, heat waves, extreme storms and how different groups of people are affected by these challenges. We know less about the impact of fluctuating winter weather and higher winds.

Climate change intensifies rainstorms.

Photo credit: Greg St. Louis

Flash floods, flash droughts

Historic precipitation patterns in Massachusetts meant small amounts of rain and snow approximately every three days. Now more of our precipitation is occurring as winter Nor’easters and summer thunderstorms and hurricanes, with longer dry periods in between. This new pattern is beginning to overwhelm aging stormwater infrastructure and stress native ecosystems.

Photo credit: Alastair McLean

Quick Take

A slowing jet stream can cause rainstorms to stall, dumping intense amounts of rain in one place.

These “cloud bursts” may not set records for total rainfall, but their intensity can cause significant short term flooding.

Elevating people and resources out of harm’s way, expanding culverts, and providing more space for rainfall to soak in all help.

Climate change means rainier winters and hotter summers.

Photo credit: Adrienne Szafranski

Our climate is moving south

According to these data from Climate Ready Boston, the number of summer days above 90 degrees F has doubled since 1990, and are expected to double again around mid-century. This means that Greater Boston summers around 2050 will be closer to those of Washington, DC’s old normal, and late century Boston will feel more like Birmingham, Alabama’s old normal. Imagine how hot it will be in Birmingham, Alabama!

Quick Take

Although epic storms and wildfires are more newsworthy, heat waves actually kill far more people.

Those most at risk during heat waves tend to be socially isolated, have underlying health issues, and lack access to air conditioning.

Heat waves often are accompanied by droughts, putting pressure on drinking water supplies, agriculture, and natural systems.

Climate change brings bigger storms.

Photo credit: Heather O'brien

Once-in-a-lifetime storms are becoming more common

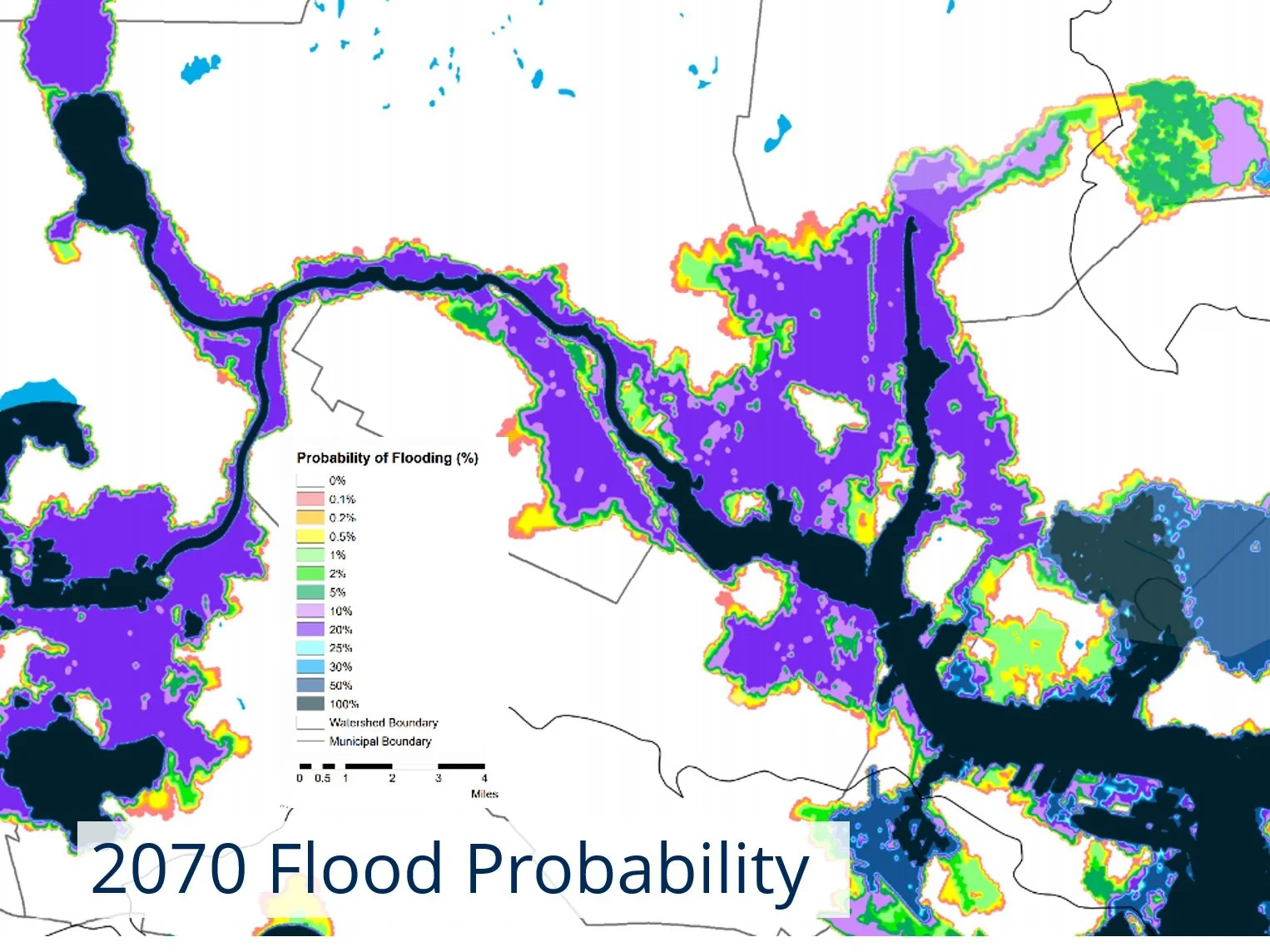

This graphic shows the likelihood of coastal flooding in the Lower Mystic Watershed around 2070 when Boston Harbor is 3 1/2 feet higher than it was in 2000. Some predictions: Downtown Malden and Medford and Cambridge’s drinking water reservoir will flood on average every five years. Parts of Chelsea, Everett and Boston will flood twice daily.

Credit: Woods Hole Group

Quick Take

Business-as-usual global carbon emissions could mean up to 7.5 feet of sea level rise in Boston Harbor by 2100.

Another way to think about sea level rise is coastal retreat.

With that much sea level rise, what was once a “100-year storm” becomes the twice-daily high tide.

Some people are affected more by heat and storms than others.

Photo credit: Wicked Cool Mystic team

People need to be able to get out of harm’s way

Extreme weather hits some people harder than others. People with greater exposure, such as outdoor workers or greater sensitivity, such as people in poor health, are affected more by heat waves and storms. People who lack the financial or emotional resources have lower adaptive capacity to recover. These three characteristics differ among populations and affect their vulnerability to climate change.

Credit: IPCC

Quick Take

Although weather is not biased, existing and past policies and investments have put some people in harm’s way more than others.

For example, “redlining” maps from the 1930s indicating bank disinvestment areas almost perfectly predict urban heat islands today.

Pre-existing traumas, financial insecurity, racism, and other socioeconomic challenges increase people’s vulnerability to extreme weather.

Climate change can also make pre-existing threats much, much worse.

Photo credit: Elle Baker

Risk Multipliers

Climate-driven extreme weather acts as a risk multiplier, making pre-existing vulnerabilities much, much worse. Wind, heat, heavy rainfall, and coastal flooding can increase people’s exposures to toxic chemicals both during and after extreme weather events. As the Mystic River watershed has many historical and current industrial sites, we are working to identify increased risk of chemical exposure over time.

Credit: David Mussina

Quick Take

Climate change is a risk multiplier. For example, if a heatwave leads to a power blackout, their combined effects on worker and resident health will be far worse than just one or the other.

Repeated exposures can add up and lower thresholds for people experiencing mental and physical health issues.

One of the biggest indicators of climate risk is the inability to get out of harm’s way, whether due to poverty, language isolation, dependent family members, or other socioeconomic challenges.

We are pragmatic, solution-oriented, collaborative and generous.

Photo credit: Chris McIntosh